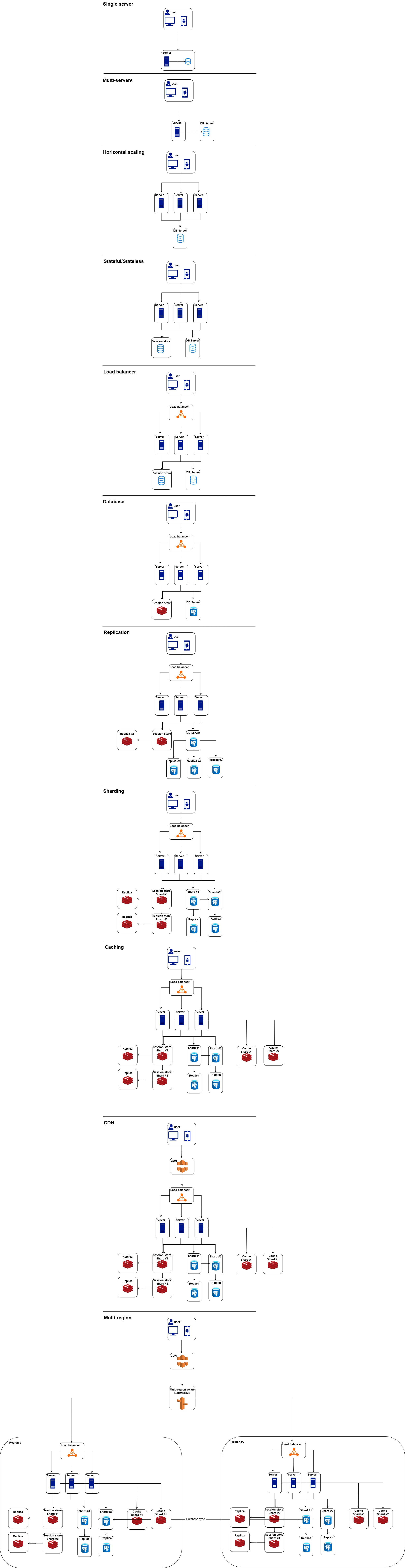

Massively scaling a web application

As user demands grow, scaling becomes critical. Whether it’s handling a surge in traffic, managing increasing amounts of data, or ensuring high availability, scaling ensures that an application remains responsive and reliable under varying workloads. The process involves strategically optimizing and expanding the infrastructure to meet the demands. This can be done vertically by enhancing the capabilities of existing servers or horizontally by adding more machines or nodes to distribute the load.

In this article, we’ll explore the core principles of application scaling, the strategies available, and some of the trade-offs involved. We’ll explore into technical considerations like managing databases, caching, and load balancing, while also addressing common challenges like cost, latency, and architectural complexity.

Single server setup

A single server setup is an attractive option for software development due to its cost efficiency, as it avoids the expense of multiple physical or cloud servers, and its simplified management with centralized configuration reducing complexity. It involves hosting all components of a development environment, such as a database and an application service. It’s ideal for small teams or projects with low traffic and manageable user bases, offering quick and easy deployment compared to distributed systems.

However, it has limited scalability for high-traffic applications, vulnerability to a single point of failure where downtime affects the entire system, and potential resource contention as multiple services share the same resources under load. This setup should be upgraded when user demand grows, and the server struggles to handle the load, frequent deployments and/or uptime requirements.

Vertical scaling

Vertical scaling, or scaling up, refers to increasing the capacity of a single server by upgrading its hardware components, such as adding more CPUs, RAM, storage, faster network, … This approach is advantageous because it simplifies the architecture, avoiding the complexity of distributed systems, and allows applications to remain on a single machine, making data consistency and management straightforward. Vertical scaling often involves less overhead compared to other scaling strategies. It’s especially suitable for applications that are tightly coupled or require low-latency processing, such as relational databases, legacy systems, or enterprise software.

However, vertical scaling has significant limitations, the most notable being a fixed ceiling, every server/cloud provider has limits beyond which it cannot be upgraded. This can become a bottleneck for rapidly growing applications. Furthermore, we have a single point of failure, if the server goes down, the entire system becomes unavailable. On most cloud providers we can have more than 150 vCPUs and 1T of RAM, but the cost can escalate quickly, as high-performance hardware is often significantly more expensive than the equivalent processing power distributed across multiple servers.

Vertical scaling can be done by resizing virtual machines or switching to higher-tier instances on platforms like AWS, Azure, or GCP. While it’s effective for smaller systems or controlled environments, vertical scaling is less flexible in handling the unpredictable demands of large-scale or highly dynamic workloads.

Horizontal scaling

Horizontal scaling, also known as scaling out, refers to the process of adding more VMs to handle increased load rather than scaling up. This approach is widely used in distributed computing systems, cloud services, and web applications where traffic and data can grow unpredictably. One of the primary advantages of horizontal scaling is its flexibility, it allows to add capacity incrementally, making it cost-efficient for systems with fluctuating demand. Additionally, it improves reliability and fault tolerance since workloads are distributed across multiple servers, if one server fails, the others can continue to operate. Horizontal scaling is also well-suited for modern cloud architectures that leverage microservices, containerization, and orchestration platforms such as Kubernetes, and is ideal for use cases like e-commerce, social media, and streaming services where user traffic can surge rapidly and unpredictably.

However, horizontal scaling comes with challenges, including increased complexity in management and coordination between servers.

Stateful vs stateless applications

Stateful and stateless applications are distinguished by how they handle and maintain data, particularly user session information and interaction contexts. In a stateful application, the server retains information about the client across multiple requests, creating a “state” For example, in a web application, a user’s login session, shopping cart data, or game progress are stored on the server-side. This is typically achieved through session management systems, cookies, or an external storage (database, …). Stateful applications are vital for user experiences that require continuity, such as e-commerce platforms, banking applications, and collaborative tools. They excel in providing seamless user interaction but come with technical complexities, especially when scaling. Horizontal scaling, for example, requires mechanisms like session replication across servers or sticky sessions to ensure the user’s state is consistently accessible. This can increase latency and add complexity.

In contrast, stateless applications do not store client-specific data between requests. Each request from a client contains all the information necessary to process it, and the server treats every interaction as independent. This architecture aligns well with protocols like HTTP, which are inherently stateless, and is a cornerstone of RESTful APIs and serverless computing. Stateless designs are advantageous for scalability and reliability because servers can handle any request without context. This simplifies load balancing (next chapter) and makes recovery from failures easier, as no session data is lost. However, stateless applications offload the responsibility of maintaining state to the client.

Technical differences between these models highlight their strengths and weaknesses. Stateful applications often require a database or memory cache to store session data, which can lead to bottlenecks in performance and challenges in maintaining consistency across distributed systems. Techniques like database sharding or distributed caches (e.g., Redis or Memcached) can help mitigate these issues but add to architectural complexity. Stateless applications, on the other hand, often rely on idempotent operations and external storage (e.g., a database) for retrieving and processing repeated context.

In terms of use cases, stateful applications are critical for workflows involving complex, multi-step, secured interactions where session continuity is required, such as online banking. Stateless systems shine in environments demanding rapid scaling and simplicity, such as in a microservices or serverless architectures.

Both models have their limitations. Stateful systems risk downtime or data loss if the server handling the state crashes, making failover configurations more complex. Stateless systems, while scalable, can become inefficient when handling interaction-heavy workflows, as the repeated transmission of context data burdens both clients and servers. By understanding the trade-offs and technical considerations of stateful and stateless architectures, developers can select the model that best meets the scalability, performance, and user experience requirements of their applications.

Load balancer

A load balancer is a critical network component designed to distribute incoming traffic or workloads across multiple servers to ensure no single server becomes overwhelmed, improving the reliability and performance of applications. Load balancers can operate at different levels of the OSI model, such as Layer 4 (transport level) for TCP/UDP traffic or Layer 7 (application level) for HTTP/HTTPS requests. By spreading requests evenly, they maximize resource utilization and minimize response times, creating a seamless user experience even during traffic spikes. Modern load balancers often incorporate health checks to identify and route traffic away from unresponsive or failing servers, thus enhancing system availability. They could support features like SSL termination and caching which further optimize performance.

The advantages of load balancers are numerous. They ensure high availability by rerouting traffic during server outages, prevent server overloading, and improve fault tolerance in distributed systems. They play a crucial role in horizontal scaling, enabling applications to handle increased demand by adding more servers. Advanced load balancers support global traffic distribution, allowing companies to deploy geographically distributed systems for lower latency and improved user experiences.

However, load balancers add an additional layer of complexity and cost to infrastructure. Their performance becomes a bottleneck if not properly sized, and in some cases, they can become a single point of failure themselves unless deployed in a highly available configuration, such as with redundancy or failover mechanisms, and they might introduce latency.

Choice of database

Databases are fundamental to storing, managing, and retrieving data, with various types designed for specific use cases, each with distinct architectures and trade-offs. Relational databases (RDBMS), like MySQL and PostgreSQL are structured and use tables with predefined schemas. They rely on SQL for queries and emphasize ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) properties, ensuring high reliability and data integrity. These are ideal for applications needing complex relationships and queries, such as ERP systems, e-commerce sites, and financial applications.

NoSQL databases, represents document, key-value, column-family, and graph databases, are more flexible and scaleable, often trading off strong consistency for availability and partition tolerance (AP as per the CAP theorem). Document stores like MongoDB and Couchbase handle semi-structured data using JSON-like documents, making them suitable for content management systems or rapidly changing schemas. Key-value stores, such as Redis and DynamoDB, offer lightning-fast read/write performance for scenarios like caching, session management, or leaderboards but lack sophisticated querying capabilities. Column-family databases like Cassandra and HBase are optimized for big data and time-series analysis, excelling in write-heavy workloads. Graph databases, like Neo4j, are specialized for exploring and analyzing relationships, such as in recommendation engines or social networks.

NewSQL databases, such as CockroachDB or VoltDB, attempt to combine the scalability of NoSQL with the ACID guarantees of traditional RDBMS.

To choose the right database, start by evaluating your data’s structure, volume, and access patterns. If your application involves structured data with complex relationships and demands strong consistency, an RDBMS is typically the best choice. For unstructured or semi-structured data with scalability requirements, NoSQL solutions like document stores or key-value databases are more appropriate. When data is graph-like and relationship-driven, a graph database is optimal. For use cases like high-frequency logging or monitoring, a time-series database provides performance and efficiency. Consider the read/write balance, as databases optimized for heavy reads (like caching systems) may not perform well under heavy writes.

Scalability requirements also influence the decision: vertical scaling (adding resources to a single server) suits RDBMS initially but has limits, while horizontal scaling (adding more nodes) is more naturally supported by NoSQL systems. Operational complexity, licensing costs, and integration with existing technology stacks are also crucial. Increasingly, modern systems employ polyglot persistence, combining multiple database types to leverage the strengths of each for different components of an application. For example, a system might use a relational database for transaction records, a document store for user-generated content, and a key-value store for caching.

Understanding the trade-offs between consistency, scalability, performance, and complexity will guide your choice, ensuring that the database fits your application’s unique needs.

Database replication

Database replication is the process of duplicating data across multiple servers to ensure reliability, improve performance and enhance scalability. It involves copying data changes made on one database named the master node, to one or more other databases called replicas, enabling a distributed data architecture. There are various types of replication strategies, each tailored to specific application requirements. Synchronous replication ensures that data is written to both the master and replica nodes simultaneously, guaranteeing strong consistency, as the write operation only completes when all replicas confirm the transaction. This method is ideal for critical applications like financial systems, but comes at the cost of increased latency. Asynchronous replication, on the other hand, allows the master to continue processing transactions without waiting for replicas to acknowledge the changes. While this improves performance and reduces latency, it introduces the risk of data lag or eventual consistency.

Multi-master replication allows updates on multiple nodes, enabling high availability and write scalability, but it introduces challenges in resolving conflicts when the same data is modified concurrently on different nodes. This strategy is common in applications requiring decentralized writes, such as distributed data entry systems or geographically distributed applications. Single-master replication, where only one node accepts writes while others serve as read-only replicas, simplifies conflict resolution and is widely used for read-heavy workloads like analytics or high-traffic web applications. Bidirectional replication, a subset of multi-master replication, allows two nodes to act as both master and replica for each other, often used in active-active failover setups. Filtered or partial replication replicates only a subset of data based on specified criteria, optimizing bandwidth and storage in cases where full replication isn’t necessary.

Cloud-native databases often support advanced replication mechanisms, such as global replication, which provides low-latency access across geographically distributed regions by replicating data closer to users. Amazon Aurora and Google Spanner are examples of managed database services that incorporate replication as a core feature to enhance availability and scalability.

The advantages of replication are significant. It increases data availability by providing failover mechanisms, if the master database fails, replicas can take over, ensuring minimal downtime. It enhances scalability by offloading read operations to replicas, freeing up the master for write-heavy tasks. Replication also supports disaster recovery and backup strategies, as replicas can serve as live backups. Additionally, replication can improve performance for distributed systems by reducing latency, allowing users to access data from the nearest replica.

However, replication adds complexity to database management, requiring careful configuration and monitoring to ensure data consistency and synchronization. In asynchronous replication, the risk of data lag or divergence between the master and replicas must be managed, particularly for applications requiring strong consistency. Synchronous replication can degrade performance due to the overhead of waiting for multiple nodes to acknowledge transactions. Network bandwidth and storage costs increase with the number of replicas. Additionally, replication does not inherently solve scalability for write-heavy workloads unless combined with other techniques like sharding (which we will discuss next).

In practice, choosing a replication strategy depends on the specific requirements of the application. For mission-critical systems, synchronous replication is preferred for consistency, while asynchronous replication works well for read-heavy distributed workloads.

PostgreSQL uses streaming replication and logical replication for real-time synchronization, while MySQL supports replication through binlogs. Cloud providers like AWS, GCP, and Azure offer managed replication services as a package with automated failover, backup, and monitoring.

Replication is a cornerstone of modern distributed database architectures, enabling the high availability, scalability, and resilience required by today’s data-intensive applications.

Database sharding

Database sharding is a technique used to partition data across multiple servers, or “shards,” to improve performance, scalability, and manageability in systems handling massive amounts of data. The fundamental principle involves splitting a single large database into smaller pieces called shards, where each shard operates as an independent database containing a subset of the data. The most common method of sharding is horizontal partitioning, where rows of a table are distributed across different shards based on a sharding key.

One of the key advantages of sharding is its ability to enhance scalability, by distributing data across multiple servers, sharding allows the system to handle a much larger workload than a single server could while improving performance. Sharding can improve fault tolerance and availability as well, if one shard fails, others can continue to operate.

The choice of a sharding key is critical, as a poorly chosen key can lead to unbalanced shards and degrade system performance. Managing cross-shard queries is another challenge, operations like joins, aggregations, or transactions that span multiple shards are more complex/expensive and requires coordination between shards, which can result in higher latency.

Caching

Caching is a technique used in software to store copies of data in a location that is faster to access than the original source, reducing latency and improving system performance. It’s a cornerstone of modern computing, used in everything from CPU operations to large-scale distributed systems like CDNs (next chapter) and web applications. The primary goal of caching is to reduce the time and resources needed to fetch frequently used data by keeping it closer to the application or end-user. Caches can exist in various layers of a system, such as in-memory caches (Redis or Memcached), disk-based caches, or client (browser, phone, …) caches, depending on the requirements of the application.

It can dramatically improves performance by reducing the time to retrieve data, especially when fetching from slow sources like databases, APIs, or remote servers, or doing intensive calculations. This leads to a better user experience, as pages load faster and applications respond more quickly. Caching also reduces the load on backend systems, since frequently accessed data doesn’t have to be repeatedly computed or fetched. It’s also a key enabler for scalability, allowing systems to handle a larger number of users without requiring proportional increases in infrastructure. In distributed systems, caching minimizes the latency associated with network hops by placing data closer to the point of consumption.

However adding a cache isn’t always a straighforwad operation, especially while maintaining data consistency in dynamic applications with frequent data changes. Cached data can become stale, leading to incorrect or outdated information being served to users. Managing cache invalidation (updating/removing outdated entries) is notoriously difficult and is often referred to as one of the hardest problems in computer science (along with naming). Over-caching or under-caching can also pose problems. If too much data is cached, it can exhaust memory, while insufficient caching could fail to deliver performance targets.

Hence, Determining what to cache and for how long is critical. we must identify data that is frequently accessed and unlikely to change rapidly to maximize the cache’s effectiveness.

There are three common invalidation strategies: time-based expiration (TTL), manual invalidation, and event-driven updates.

Cache misses—when data is requested but not found (not yet loaded, or was invalidated) in the cache which can lead to performance hits as the system falls back to the slower original data source, negating some of the cache’s advantages. Similarly, cache thundering or stampeding occurs when multiple requests simultaneously attempt to fetch the same missing item, overwhelming the backend.

For write-heavy applications or scenarios where every data fetch involves unique or constantly changing information, caching might provide little to negative benefits. Poorly configured caching can lead to security risks, such as exposing sensitive data to unauthorized third parties.

In web development, it powers faster page loads by caching static assets like images, CSS, and JS files. In databases, query caching reduces repetitive reads for commonly accessed data. On a smaller scale.

CDN

A Content Delivery Network (CDN for short) is a distributed network of servers designed to deliver web content, such as images, videos, stylesheets, scripts, … to users more efficiently by serving them from geographically closer locations. CDNs improve performance by reducing latency, minimizing the distance data travels, and offloading traffic from the origin server, enabling faster page load times and a better user experience. They are essential for high-traffic websites, global applications, and services requiring low-latency delivery, such as video streaming. They allow to better handle spikes of traffic, enhanced reliability through redundancy, and they have built-in security features like DDoS mitigation.

Multi-region deployment

Multi-region deployment refers to deploying an application across multiple geographic regions to improve performance, reliability and scalability. This strategy enables faster response times for users by serving content from the nearest location and enhances fault tolerance by reducing the risk of service outages due to regional failures, such as natural disasters or localized infrastructure problems.

Multi-region deployment improves latency because users are directed to the nearest server. It also enhances availability and resilience, if one region experiences downtime, traffic can be rerouted to other regions, ensuring continuous operation.

However, implementing a multi-region architecture is complex. Synchronizing data across regions is challenging, as maintaining consistency often involves trade-offs between performance and strict ACID properties, also, it can cause potential latency for synchronization tasks, such as replicating databases, which can slow down write-heavy applications, moreover, compliance regulations might restrict certain data from being transferred between regions.